Metabolic Adaptation: What Is It, Why It Happens, & How to Reduce The Effects

Table of Contents

- What Is Metabolic Adaptation?

- Understanding Energy Balance

- Why Does Metabolic Adaptation Happen?

- Hormonal Changes

- Starvation Mode and Metabolic Damage

- How You Can Reduce The Effects of Metabolic Adaptation

What Is Metabolic Adaptation?

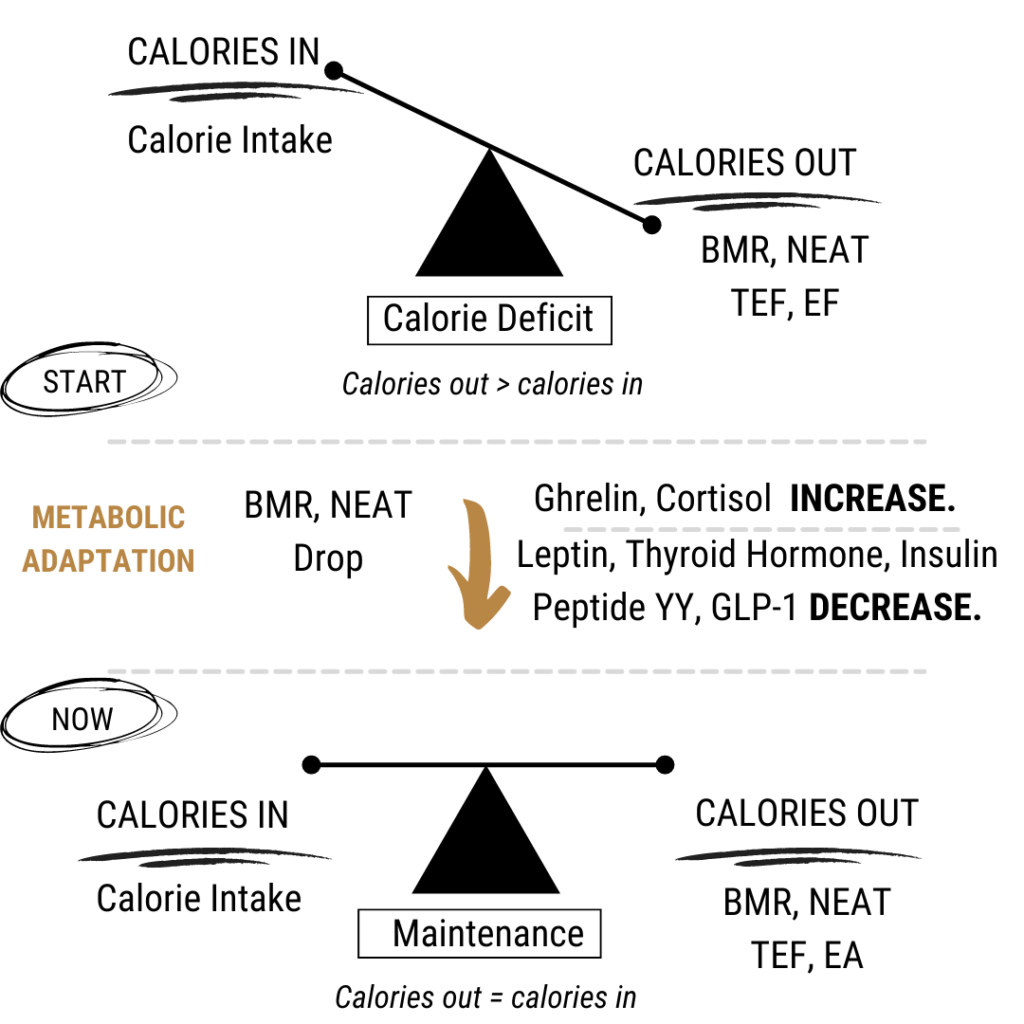

Metabolic adaptation refers to the various changes that take place in your body to reduce energy expenditure (burn less calories) in order to conserve energy. Your body becomes more efficient at using the energy you provide your body with. This happens in response to the calorie deficit you create as you try to lose weight.

Have you ever had a time where you initially lost a good amount of weight, then plateaued and stopped losing weight? You keep eating the same amount of calories, you’re keeping up with your activity level, and you’re doing everything the same that resulted in the weight loss in the beginning, but now, the scale just won’t move. You can’t lose any more weight, and you have no idea where you’re going wrong. If you’ve been through this, there’s a good chance you’ve experienced the effects of metabolic adaptation.

Understanding Energy Balance

To understand metabolic adaptation better, it’ll help to understand energy balance.

Energy is another word for “calories.” So energy balance refers to the amount of calories being consumed vs. the amount of calories being burned.

You’ll often see this referred to as “calories in vs. calories out.”

You’re in a positive energy balance if you’re consuming more calories than you’re burning. Calories in is greater than calories out. This results in weight gain.

You’re in a negative energy balance if you’re burning more calories than you’re consuming. Calories in is less than calories out. This results in weight loss.

You’re in a neutral energy balance when you’re consuming the same amount of calories that you’re burning. Calories in equals calories out. When calories in equals calories out, you will maintain your current body weight.

The “calories in” side of the equation consists of your calorie intake, but there are many factors that can make controlling your intake a challenge. You’ll see what those are later on.

These are the four components of your TDEE (Total Daily Energy Expenditure). These make up the “calories out” side of the equation.

- BMR (Basal Metabolic Rate): The number of calories your body needs to perform basic, life-sustaining functions while at rest. Your BMR accounts for roughly 60-70% of your TDEE.

- NEAT (Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis): This includes calories burned through daily physical activity and movement that is not planned exercise or sports. Examples include walking, typing, fidgeting, cleaning, yardwork, etc. This accounts for about 15% of your TDEE, but it can vary a lot person to person. In very active people, it can make up roughly 30% of their TDEE.

- TEF (Thermic Effect of Food): The number of calories burned digesting and absorbing food. This accounts for approximately 10% of your TDEE.

- EAT (Exercise Activity Thermogenesis): The number of calories burned during exercise. EAT accounts for roughly 5% of your TDEE.

So, if you want to lose weight you must be in a calorie deficit, or a negative energy balance. There’s no other way around it.

You do this by adjusting your calorie intake, your activity level, or a bit of both. Ideally, both would be adjusted. You’d reduce your calories so you’re in a calorie deficit, or in a negative energy balance, and you would increase your activity level.

Your diet will be the primary driver of fat loss. So don’t try to out-exercise a poor diet.

You might see some people oversimplifying fat loss and saying it’s all about calories in vs. calories out. While it is primarily about calories in vs. calories out, there are many things that can influence both sides of the equation.

Energy balance is not static. It’s dynamic and is constantly changing as your body changes.

There are many things that can influence either side of energy balance.

First, larger bodies tend to require more energy, or calories, and they also burn more calories when exercising. Smaller bodies are the opposite. They often require less calories, and burn less calories during exercise.

So, as you lose fat and overall body mass, and weigh less, you burn less calories because you’re now smaller than you previously were. This decreases the calories out side of the equation.

This drop in body mass that requires less calories is separate from a drop in metabolic rate. These are not the same thing, and they don’t drop in proportion to each other.

This is one of the reasons why so many people struggle to keep the weight off after losing it.

This one two punch of a drop in your calorie requirement after weight loss and a drop in metabolic rate changes the calories out side of the energy balance equation even more.

There are other changes that influence energy balance as well.

When you’re in a calorie deficit and dropping weight, your hunger hormones that regular your appetite and satiety start working against you, making you more hungry and wanting more food.

You also start unconsciously moving less. Remember, the main purpose of metabolic adaptation is to conserve energy and prevent us from starving and eventually dying during times of famine. Today, going on a diet is the closest thing to a famine most of us will ever experience, but your body still perceives it the same.

So, as you spend time in a calorie deficit and lose more weight, you’ll start moving less, without even realizing it. You’ll fidget less, you probably won’t get up to grab more water as frequently, you’ll move slower, and you’ll probably take the shorter route when walking your dog. Those are just some examples, but you’ll start moving less and slower in the smallest ways, but this all adds up to decrease what’s called NEAT (Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis). This is all activity that does not include exercise, like typing, walking, cleaning, yardwork, walking to your car, fidgeting, cooking, etc.

NEAT contributes to the calorie out side of the equation since this is calories burned. And NEAT can vary a lot person to person. Those who are very active can burn several hundred calories from NEAT alone. A drop in NEAT as someone loses weight is one of the biggest contributors to metabolic adaptation. This decreases the calories out side of the equation since you’re burning less calories.

In addition to a drop in NEAT, you’ll most likely experience a drop in training intensity, effort, and endurance during your workouts as you diet. This can also impact the calories out side of the equation. Oftentimes this drop in the quality of your training isn’t even that noticeable. At least not until you start eating more, and then you realize how much harder and longer you can train now that you’re eating more.

Now you see why weight loss is never linear. Your weight will fluctuate throughout the process. You’ll hit plateaus, you’ll have times your weight jumps up or down more than expected, and you’ll have times you’re making great progress for weeks, and then get stuck for weeks. It’s very unpredictable because as we mentioned earlier, energy balance is not static and it’s constantly shifting.

Why Does Metabolic Adaptation Happen?

Years ago metabolic adaptation served us well and protected us. It was an evolutionary advantage that prevented us from starving to death during times of famine.

During these periods of time when food was extremely scarce, our bodies adapted to the lower calorie intake by conserving energy and becoming more energy efficient. Back then, this was great. It protected us and helped us survive during these times rough times.

If you’re able to access the internet and read this, food availability is probably not an issue. There’s an overabundance of food. The problem is that our biology hasn’t changed much at all over the years.

When we go on a diet to lose weight and we restrict calories, our bodies view that calorie restriction the same way it responded to famine years and years ago. The problem is, our bodies are detecting that food is low, when its quite the opposite. Food is overly abundant, and not low at all. We’re just trying to diet and not be fat.

So what once served us well and protected us from starving to death, now leaves us struggling to lose weight, and keep it off.

Our environment today is completely different, and it overrides our biology.

Today, we have ultra-processed, calorie-dense, hyperpalatable foods so easily available to us, making it very easy to get in far more energy (calories) than we need to survive.

In addition to processed, calorie-dense, hyperpalatable foods being so plentiful, making it very easy to overeat, we’re also far less active than we were years and years ago.

Thousands of years ago we had to walk everywhere we traveled to, we hunted our own food, and built our own shelter. Compared to today’s standards, we were extremely active then.

Now we have cars, trains, airplanes, boats, elevators, escalators, motorized scooters, and most people sit for hours and hours a day and get food delivered straight to their door.

Put an organism with the human biology in the environment we live in today, and becoming overweight is too easy. Back in the day, the combination of a very high level of activity and food being scarce, being lean was easy, and being overweight was probably unheard of.

Hormonal Changes

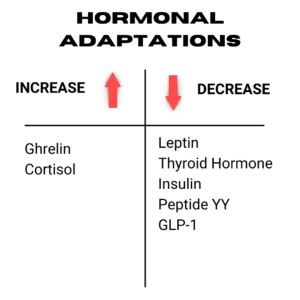

There are many hormonal changes taking place as you spend time in a calorie deficit and lose weight. These hormonal adaptations that take place make it more difficult to sustain a calorie deficit. The changes that occur are basically trying to get your to seek out food, and eat more.

Ghrelin

Ghrelin is a hormone that increases appetite. It’s produced in your stomach and secreted when food is low. It enters the bloodstream and affects the hypothalamus of the brain, which then stimulates your appetite and increases hunger.

When you’re dieting and losing weight, ghrelin increases, and that makes you hungrier.

Leptin

If you ever hear the term “hunger hormones,” they’re mainly referring to ghrelin and leptin.

Leptin is produced by fat cells in your body, and when released, it signals to your brain that you have enough food and don’t need to eat.

When dieting to lose weight, leptin levels decrease, which then increases hunger.

As you lose weight, ghrelin increases and leptin decreases, both contributing to making your more hungry.

Thyroid Hormone

Thyroid hormones (T3 & T4) help regulate your metabolic rate. Many of your body’s cells have thyroid hormone receptors, which means that thyroid hormones can influence your metabolism in a variety of ways. As you lose weight, thyroid hormone decreases, which then decreases your metabolic rate

Cortisol

Cortisol is a hormone that is known for increasing during times of stress, both physiological and psychological stress. You’ll often see it referred to as the “stress hormone.”

Restricting calories is a form of stress to the body. So as you spend time dieting in a calorie deficit, cortisol levels will rise. As cortisol levels rise, your appetite can increase, and so can your cravings for high-fat, sugary or salty foods that are loaded with calories.

Cortisol can also rise due to physical stress from training, and psychological stress due to relationships, work, family, school, personal issues, anything in life that is stressing you out and has you worried.

So combine a low-calorie diet with intense training and psychological stressors life throws at you, and your cortisol levels can be quite high at times.

An increase in cortisol can cause water retention. This increase in water retention can mask fat loss. You might look in the mirror and appear softer. You might weigh yourself and see the scale hasn’t moved one bit. Now you’re frustrated you’re not losing weight even though you’re doing everything right. You might actually be losing body fat, but the increase in water retention can cause the scale to rise and make you look like you haven’t lost weight, even if you have.

Insulin

Insulin is a hormone that is produced and secreted in the pancreas. It’s secreted in response to glucose circulating in the blood stream (like after you’ve eaten).

Insulin enters the blood stream and moves the circulating glucose into your cells to use for energy later on. When this happens, blood sugar (glucose) levels go down.

In other words, insulin allows your body to use glucose for energy, and regulates blood sugar (glucose) levels.

When insulin levels are higher, it sends a signal that energy is available. This energy gets stored, and signals the body and to stop eating.

Insulin levels drops when calories are restricted and that sends a signal that energy is needed, and promotes food intake.

GLP-1 (Glucagon-like Peptide-1)

Dieting is linked to a decrease in GLP-1. When this hormone decreases as you lose weight, you’re more likely to not feel as full between meals, which can increase appetite and making it more difficult to not overeat. This is a contributor to weight regain after dieting and losing weight.

Peptide YY

Peptide YY is a hormone that’s produced and secreted in the small intestine. It helps you feel full after eating and reduces appetite. It also slows down the speed of food moving through the digestive tract. Peptide YY decreases when food is low. Similarly to GLP-1, this makes you not feel as full after eating.

You’ll often see people blaming their hormones for their lack of weight loss. Or, they’ll claim they have to first balance their hormones in order to lose weight. Both of these ideas are incorrect.

Hormones can impact energy balance by increasing your appetite and hunger, making it more difficult for you to eat less and remain in a calorie deficit. But this doesn’t mean hormones are to blame entirely. These hormonal changes happen to everyone, some more than others, who loses weight.

At the end of the day, weight loss still comes down to consistently being in a calorie deficit. You must consume less calories than you burn. You must be in a negative energy balance.

This is why oversimplifying weight loss and telling someone calories in vs. calories out is all that matters, and all they have to do is be in a calorie deficit isn’t helpful in most cases.

Starvation Mode and Metabolic Damage

If you’re reading this, I’m sure you’ve heard the terms “starvation mode” and “metabolic damage.”

Many people blame their lack of weight loss on being in starvation mode, or being metabolically damaged. You’ve either done this yourself, or you’ve hard some suggest that one of these two things is the reason you, or they, are not losing weight.

Let’s take a look at each term and break down what’s actually happening when you think you’re in starvation mode, or are metabolically damaged.

Starvation mode

I’m sure you’ve heard someone say it. They’re talking to a friend or family member who’s been desperately trying to lose weight, and they tell them “you’re not losing weight because you’re eating too little, your metabolism has slowed down so much, and now you’re in starvation mode!”

This idea of starvation mode being the reason you’re not losing weight is completely wrong. You might even hear these same people struggling to lose weight say that they’re gaining weight in starvation mode. This is typically followed up by someone giving them the advice of “you just need to eat more to lose more!”

So wait, if you eat too few calories for too long, you’ll go into starvation mode and start gaining weight?

If this were true, there wouldn’t be any starving, malnourished people in world. You’d go to an impoverished third world country and everyone would be overweight because they’re in starvation mode. But that’s not how it works. You hardly see any overweight people walking around in poverty-stricken areas where food is scarce. Instead, you see lots of extremely thin, underweight people. Some that are actually truly starving. N one will ever start gaining weight and become overweight from eating too few calories.

And the claim that if you want to lose weight, you should start eating more? Maybe you should eat a bit more if you’re in too large of a calorie deficit. But you’d still be in a deficit, just not as large of one. But the idea of eating more to lose more is just wrong. Have you ever seen an overweight person start eating even more than they previously were, and then lost weight? Of course not.

Now, what some people might mean by eating more to lose more is that they eat more food in volume. Meaning their food quality improved, they’re eating more fruits, vegetables, lean protein and other nutrient-dense foods that are lower in calories and more filling. These foods contain less calories, but take up more room on your plate and in your stomach compared to a fast food and other processed snacks. So yes, you’re eating more in regards to food volume, but your calories are lower.

So, what’s actually happening when you think you’re in starvation mode?

Oftentimes, you’re experiencing the effects of metabolic adaptation.

As Dr. Eric Trexler said it here in this interview with Jeff Nippard, starvation mode is a “dramatic interpretation of metabolic adaptation.”

You were losing weight, but now you’re stuck. The number of calories that was a deficit in the beginning is now your new maintenance.

So in order to continue losing weight, you need to either further reduce calories, increase activity level, or a bit of both. If you’ve been dieting for 12 weeks or more and your biofeedback (sleep, energy, mood, hunger, cravings, etc. ) aren’t looking too good, a diet break may be a good idea.

But you’re NOT in starvation mode. This isn’t even a scientifically valid term, and it doesn’t exist the way people think it does. Starvation mode is exactly what it sounds like–people that are literally starving, which most likely isn’t you.

If you start gaining weight, it’s often because your activity level has reduced without you even realizing it. Your NEAT (Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis) which can make up a good chunk of your total daily energy expenditure, drops because your body is trying to conserve energy by moving less, and expending less energy (calories).

So if your NEAT drops, you’re no longer burning as many calories as you used to. On top of that, maybe you haven’t made any changes to your calories. What was a calorie deficit in the beginning is now your new maintenance. So, you’re eating at maintenance calories and you reduced your activity level. Now you’re in a calorie surplus. This can explain a plateau and then some weight gain after you’ve been dieting for a while.

The best thing you can do is be conscious of this and keep your activity level up. This is why step trackers can be a great tool for measuring your activity level. Even if it’s not that accurate, if your step count is going down, you know you’re becoming less active and need to move more.

Another reason you might think you’re in starvation mode is that you’re miscalculating how many calories you’re consuming. The participants of this study underestimated their calorie consumption by about 37%. That can definitely be enough to prevent you from losing weight.

If you remember from the hormonal adaptations section, cortisol levels rise when calories are restricted for an extended period of time. This can cause more water retention. At times, water retention can mask fat loss. So you might be losing fat, but the excess water retention is making it difficult to notice, and the scale isn’t moving. Also, women going through their menstrual cycle will often retain more water and gain weight during this time.

To get rid of or reduce water retention, you can avoid dieting too aggressively, limit sodium intake, have more potassium, get plenty of sleep, include refeeds, manage stress level, maybe even take a deload week from training, and drink more water. I know, it sounds backwards. But yes, drinking more water can help reduce water retention.

Starvation mode is definitely not the reason you’re not losing weight, and it doesn’t exist.

Your body is changing and adapting to weight loss as you diet, you might be misreporting your calorie consumption, and water retention could be masking fat loss.

Metabolic Damage

Another term you’ll see used a lot is “metabolic damage.” Many people believe they can’t lose weight because they’ve been eating so few calories and they’ve damaged their metabolism.

When you enter a calorie deficit, sustain that for a period of time, and lose weight, your metabolism will slow down. It’s unavoidable. It’s also not permanent. There are steps you can take to reduce the down regulation of your metabolism. Even when it has slowed down by quite a lot, it can be improved and recovered.

More aggressive weight loss approaches where large calorie deficits are used to drop a lot of weight very quickly will make the metabolic down regulation more severe. Your metabolic rate will slow down even further than if you would have taken a more modest approach and lost weight at a slower rate, kept protein high, and lifted weights. The greater the severity of the metabolic down regulation, the more time and effort it’ll take to recover from it. Another common mistake made, mainly by women, is avoiding all weight lifting, or going very high reps and light weight, but doing tons of cardio. Combine that with a deficit, and it’s a great way to lose a good amount of muscle. The more muscle you lose, the more your metabolic rate will drop.

So no, your metabolism is not damaged. Your metabolic rate is just much lower than predicted. This often happens in people who go through what they call “yo-yo dieting.” This is where there’s big fluctuations in weight. They gain a lot of weight, then try to lose it all quickly, and they’re in this constant cycle of gaining and losing, usually spending more time in a calorie deficit trying to lose weight.

Your metabolism can be improved over time with some effort and patience, and it may be lower than expected based on your age, height, and weight, but it is likely not damaged beyond repair.

How You Can Reduce the Effects of Metabolic Adaptation

Unfortunately, there is no way to completely avoid metabolic adaptation from happening. It will happen, but there are steps you can take to mitigate the effects and reduce the severity of the metabolic adaptation you experience as you go through your fat loss journey.

Don’t lose weight too quickly

If you lose weight too quickly, you do run the risk of losing muscle mass. One study found that people who lost 1.4% of their body weight per week lost more muscle than people who lost only 0.7% per week.

Losing 0.5-1% of your current body weight per week is the recommended rate of weight loss. At this rate, you can lose body fat and reduce your chances of losing too much muscle mass along with it.

Those who have more fat to lose, about 25% body fat or higher, can get away with losing closer to 1% of their current body weight per week. As you get leaner and lower your body fat percentage, you’ll want to lose less of your body weight each week, closer to 0.5%. This is because those who are leaner have a higher risk of losing muscle as they remain in a deficit and lose more weight. The metabolic adaptation you experience will be worse if you lose more muscle. So maintaining as much muscle mass as possible is key.

Keep protein high

Protein is the most important macronutrient when losing weight and preventing any further drops in your metabolic rate. Protein helps preserve muscle mass. Even if you’re not concerned with holding onto as much muscle as possible from an appearance standpoint, it’s important for preventing your metabolic rate from dropping too much. Muscle is very metabolically active tissue that requires more calories than fat. So if you drop muscle mass, your metabolic rate will also drop along with it.

In addition, protein does a better job of suppressing your appetite and making you feel full for longer. Ghrelin, the hunger hormone that increases when you diet and makes you hungrier, is suppressed the most by protein.

Protein also has a higher thermic effect of food (TEF) than carbs and fats. This means that your body works harder and burns more calories digesting and absorbing protein than it does carbs and fats. The thermic effect of food (TEF) makes up about 10% of your total daily energy expenditure (TDEE).

Progressive weight training

Weight training that is focused on progressive overload is another tool, and arguably the best tool, for holding onto as much muscle as possible as you lose body fat.

When it comes to weight loss, many people underemphasize weight lifting, and make the mistake of focusing too much on cardio. Cardio can burn more calories than weight lifting temporarily, but weight lifting burns more calories long-term. Weight lifting results in higher EPOC (Excess Post-Exercise Oxygen Consumption). This means your body continues burning calories longer after the workout is complete. Some say this lasts up to 48 hours, which is much longer than cardio.

In addition, excessive cardio, a lack of weight training, and a calorie deficit is a recipe for muscle loss. And as we’ve discussed, a loss of muscle results in a lowered metabolic rate, which then makes the metabolic adaptation worse.

Don’t try to train, either weight training or cardio, your way into a calorie deficit for fat loss.

Let your nutrition be the primary driver of fat loss by sustaining a calorie deficit.

Lift weights to maintain or even continue to build muscle.

Do cardio in small to moderate amounts as a tool to help contribute to the calorie deficit, and stay active in small ways throughout day to increase NEAT without stressing the body much and negatively impacting weight training performance and recovery.

Eat more fiber

Fiber improves satiation and satiety, and slows gastric emptying. This helps you feel full for longer, which can make it easier to eat less and sustain a calorie deficit. This is partly due to high fiber foods reducing ghrelin levels. If you remember from earlier in this post, ghrelin is one of the hunger hormones that increases while dieting since food is low. When you eat high fiber foods and feel more full, ghrelin is reduced, and your appetite decreases. Foods that are high in fiber are often not very high in calories, and since they make you feel more full, you don’t need to eat as much of it. So you’re getting that fullness feeling, but without a lot of extra calories.

Also, fiber stimulates GLP-1 and peptide YY secretion, two hormones that regulate your appetite and help suppress hunger when elevated.

The recommended daily intake of fiber is 38 grams per day for men and 25 grams per day for women. You’ll also see the recommendation of 14 grams for every 1,000 calories consumed.

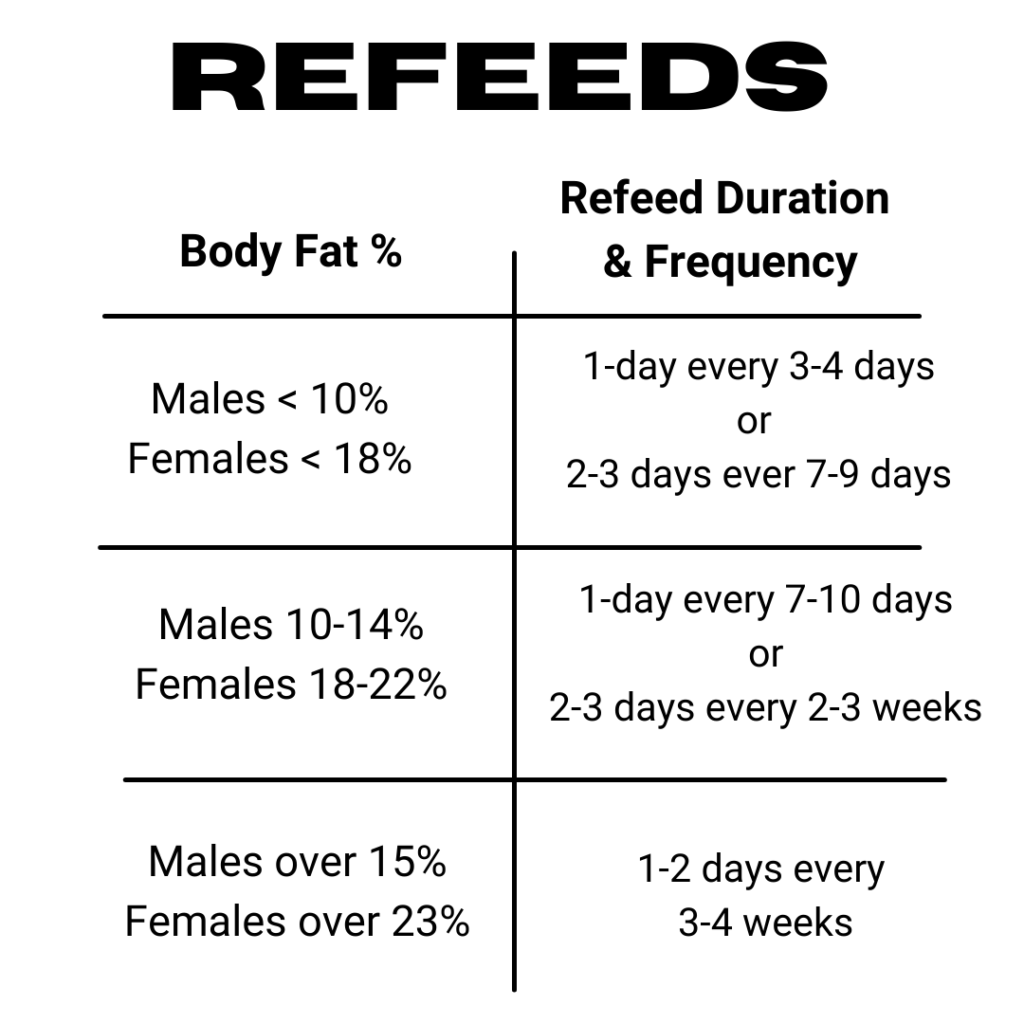

Use refeeds and diet breaks strategically

Refeeds and diet breaks are two dieting strategies that can improve adherence, enhance resistance training performance, and help preserve muscle mass.

A refeed day is a planned increase in calories, either to maintenance or small surplus, for 1-3 days. It’s intended to give your body a short break from a calorie deficit.

There are many different ways to implement them, and no on way is perfect. Their are both psychological and physiological factors to consider when deciding how to incorporate refeeds into your diet.

Generally, the leaner you are, the better off you’ll be with more frequent refeeds. Some do 1-day refeeds, and others do 2 or 3-day refeeds.

Below is a quick breakdown of how refeeds can be used. Again, there’s no single perfect way to use refeeds. You’ll see some recommend feeds at different frequencies than what I have below. It can vary a lot person to person based on how long they’ve been dieting, their psychological state, and their energy levels, mood, sleep, hunger, cravings, sex drive, and more.

Just like refeeds, there are many different ways to incorporate diet breaks into your plan.

A diet break is a planned increase in calories to maintenance that typically lasts 1-3 weeks. Like refeeds, there are both psychological and physiological factors to consider when deciding how to incorporate you diet break.

Diet breaks are often used once every 6-12 weeks, some say wait until you’ve been dieting for 14-16 weeks.

In my opinion, 14-16 weeks is a bit too long to go without one, and 6 weeks is probably a bit too soon to have one. I believe 10-12 weeks is the sweet spot, but as with most things when it comes to health and fitness, training and nutrition, it just depends on the individual.

The purpose of refeeds and diet breaks is to mitigate the effects of metabolic adaptation and improve adherence by providing breaks from dieting.

Stay active

Reduced NEAT (Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis) is a big contributor to weight loss plateaus.

As you spend time in a calorie deficit and lose weight, you’ll unconsciously begin to move less. This is your body’s way of conserving energy, without you even realizing it. Not only that, but when food is low, our energy levels can drop. So you might not be pushing yourself as hard during your workouts.

Combine a drop in NEAT and EAT, and you can see a big drop in calorie expenditure. Keep in mind too that what was once a calorie deficit for you might be your new maintenance. Combine eating at maintenance calories and a significant drop in activity level, and you’re now in a calorie surplus, and that’s how you gain weight. This is often the cause for sudden weight gain during a diet, and I mean larger amounts of weight gain, not small daily fluctuations, or changes in water retention.

So, it’s important to be conscious of your activity level. As I mentioned earlier, a step tracker is a great tool to have so you can make sure your step count isn’t dropping. Make sure you keep the training intensity and effort in the gym up as well.

Final Words

Metabolic adaptation once protected us and helped us survive, but today, it makes weight loss more of a challenge. Now that you understand what it is and why it happens, you can do what’s needed to minimize these adaptations, and get better results.

Online Coaching Application Form

Start Your Transformation Today